AIRFOIL PRIMER

FOR

NON-AERODYNAMICISTS

JOHN DREESE

&

DREESECODE SOFTWARE LLC

RED HOPE

Copyright ©

2004 by John Dreese

All rights

reserved.

Pages: 30

No part of

this book can be reproduced in any form by any means without the express

permission of the author. This includes reprints, excerpts, photocopying,

recording, or any future means of reproducing text.

Email:

DesignFOIL@gmail.com

Web:

http://www.dreesecode.com/primer/

Twitter:

http://www.twitter.com/JJDreese/

Amazon Kindle

Version available from:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/XXXXXXXX

Version 1.0

Published in the

United States of America.

PREFACE/FIGURE NAMES

This book is

the culmination of a five-part magazine article series that I wrote in 2004. It

is one of the most popular features on the DesignFOIL

website and I’ve been asked to put it in a simple Kindle format for people to

read offline.

Figures: On the website, each part is a

standalone web page and the figure numbers refer to that web page. In

this Kindle book all five web pages are combined – each one is a chapter. The

figure names refer to that particular chapter. So you might see a reference to

Figure 2. It means Figure 2 from –that- chapter.

Regards,

John Dreese

NOTE:

All airfoil shapes and data were

created using DesignFOIL. A free demo is available on

the website at www.dreesecode.com

PART 1:

WING SECTIONS & LIFT

Airshows are a

great place to study airplanes and crowd psychology. We wait patiently in long

lines for hotdogs, bathrooms and overpriced water. Of course, people do that at

all large gatherings, but the one group activity found only at airshows is the creation of

the people-filled

shadows, as

shown in Figure 1.

As the hot Sun

cooks the crowd, they migrate under the protective wing shadows of huge

airplanes, preferably a C-130 or a B-52 bomber; something with a huge wing area. And just like

that, we’ve discovered yet another practical use for airplane wings!

This primer

talks about why we have wings at all. As the aerodynamicist Jack Moran said,

wings are simply a thrust amplifier. Sure, we could use rockets to get from point A to

point B, but that would be incredibly inefficient as far as fuel usage goes.

That’s where wings come in. They provide a similar ability to defy gravity, but

at a fraction of the fuel usage compared to rockets.

Rather than use

directed raw force, wings have a unique characteristic; they generate a force

that is perpendicular to the

direction of movement. Airplanes move horizontally, but wings push up

vertically (LIFT). This magic of

physics is simply a result of how air flows over the wings. This primer series

is about how lift is created, how to estimate it, and how to make it happen.

The origin of

lift is very simple: it is the result of having lower air pressure above the wing

than below it. Air cannot impart direct forces on a wing like a hammer can.

Instead, it can only impart forces via two methods: pressure and friction. Those are the

only two ways. Lift comes from a pressure difference between the upper and

lower wing surfaces. Pretty simple eh?

No doubt, there are

many theories as to what causes the

required pressure difference. That's where people get all bent out of shape.

Blame it on Bernoulli? Blame it on momentum transfer? The devil is in the

details.

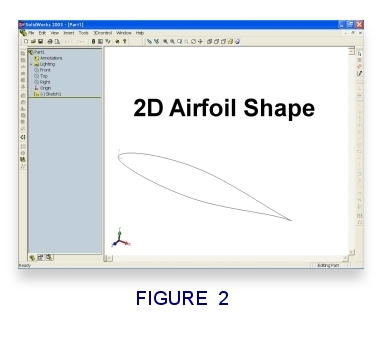

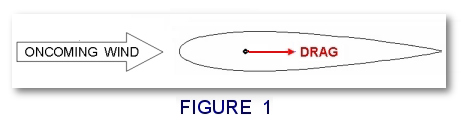

Streamlined wings

aren't the only things that can create lift; a sheet of plywood can also generate lots of

lift. Unlike a wing, of course, a sheet of plywood is aerodynamically very

inefficient. The secret to making this pressure-difference miracle more

efficient is to use a cross-sectional shape that won’t cause separation at the

nose. Plywood has a sharp leading edge which generates oodles of DRAG;

that's the retarding force that keeps us from moving forward as fast as

we’d like to. Historically, good wings use cross-sectional shapes that

are round in

the front and sharp in the back. We call this shape an Airfoil (Figure

2). There are parts of the world that use different names like aerofoil and profile.

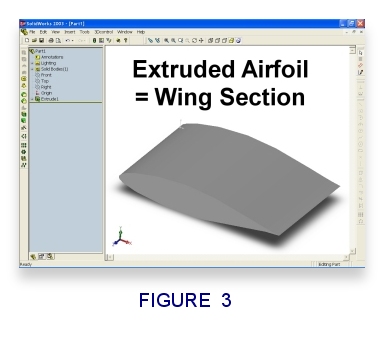

Technically,

airfoils are flat two-dimensional shapes, and can’t produce any lift at all;

great for pictures on paper, but lousy for lift. You have to extrude an airfoil into the 3rd dimension to

create an object that will make lift. We call this extruded shape a wing section (see

Figure 3).

So now you have

a device that generates a pressure difference, resulting in a vertical lift

force and a slight down-deflection of air behind it. Who cares? Millions of

airline passengers care.

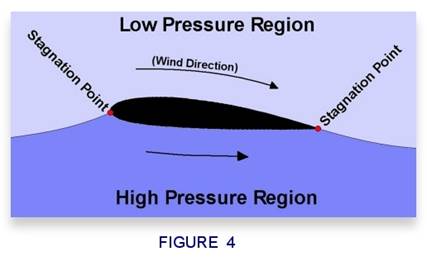

Nature will

direct the airflow around a wing section so that the air obeys the conservation

laws of mass & momentum. If the real world physics are obeyed, some of the

oncoming air will go over the wing section and some will go under the wing

section. The point on the leading edge where the oncoming flow splits is called

the stagnation

point. Strangely

enough, the velocity of air at that very point is zero. There's another

stagnation point at the trailing edge, where these two travelling air masses

come back together. Figure 4 illustrates these stagnation points.

The air pressure

along the upper and lower surfaces can vary wildly. It usually drops lower than

ambient pressure along the upper surface, especially if the wing section is

angled up at all. For a lifting airfoil, the airflow above is typically

accelerated faster than the air below. Think of it as the air up front racing

fill the void of all that air you just pushed down behind the wing. From Bernoulli's famous

effect, we know that when air speeds up, the air pressure drops. The end result

is that the pressure difference between the lower and upper surface

literally sucks

the wing upward!

To conclude the

idea, lift comes from a combined effort of the wing being sucked upwards

and the wing deflecting some of the air downward. The effects are so

intrinsically linked together that we can calculate the lift force by simply

measuring surface pressures around the wing section. That's one method which

wind tunnels use to measure lift forces and pitching moments on a wing section

model. Many advanced wind tunnels use a different technique for drag which

measures how much momentum the model "steals" from the oncoming

airflow via the boundary layer; we'll get into that later.

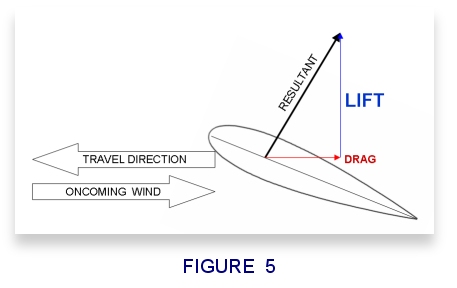

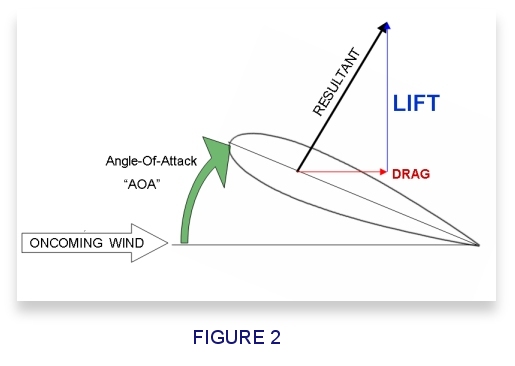

One

last note about lift. A wing section exposed to an oncoming wind

generates a single united force, usually pointing up vertically and slightly backwards. We call this theResultant force. Lift is the

portion of that force that is perpendicular to the direction of travel, not the

direction the airfoil is pointing. Drag is the

portion that is parallelto the direction of travel. See

Figure 5 for an illustration.

Now you know

where lift comes from. Next time, we'll learn the basic terms regarding airfoil

geometry.

PART 2:

BASIC AIRFOIL GEOMETRY TERMS

Subsonic airfoils

should be round

in the front and sharp in the back. A century of

visual reminders should make this obvious. However, I see it violated often

with regard to after-market wings people install on their cars. The wings are

already not very effective for the speeds that most cars are driven, but they

are -really- ineffective when mounted backwards. Remember: put the round end

upstream and the sharp end downstream. That's really the big rule at the core

of standard airfoil setup. Everything else is just tweaking and

optimization. For our purposes, all airfoil diagrams shown in this primer

series assume air movement from left to right.

Let's look at an

example:

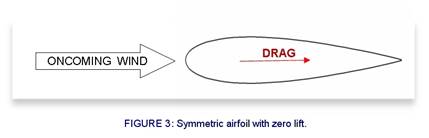

Take a symmetric

airfoil and point it directly into the oncoming wind as shown inFigure 1. Since the

airfoil is parallel with the wind, we can’t measure or feel any perpendicular

forces (up or down in this case). The lift is zero. However, there is a

slight tugging

force from

the friction of air dragging along the airfoil surface. We call this

force drag.

You might wonder

what use could come from a symmetric airfoil oriented parallel to the wind? It makes for a perfect streamlined fairing, a shield that hides some underlying

non-streamlined structure like a wire, antenna, pipe, or landing gear strut.

Streamlining is

nice, but we want lift. Let’s gently tip the airfoil up to some small angle as

shown inFigure 2. Suddenly,

there is a noticeable force upwards while the dragging force increases

slightly. What you’ve just discovered is that an increase in the angle between

the chordline of the airfoil (an imaginary straight line

stretching between leading edge and trailing edge) and the oncoming wind will

increase the lifting force. This variable angle is called the Angle-Of-Attack, or AOA for short.

What you need to know is that increasing the AOA will increase both the lift

force and the drag

force. This effect will continue up until about 15 degrees. After that, the

lift force will start to fall, but drag will continue to grow. We call this

phenomenon stall. It is the

result of the formerly smooth air over the wing breaking down and separating

from the wing. One special note: if the airfoil has upward bow to the shape (camber), then

increasing the angle-of-attack may actually decrease the drag force for a few

degrees before it resumes its quick climb.

Angle-Of-Attack is the angular

difference between where the wing is pointing and where it is moving. The first

time I truly understood this was when, as a kid, I saw a Boeing jet climbing

very slowly away from Columbus International Airport in Ohio. It appeared to be

just plowing through the air nose-high. The airplane nose will not always point

straight in the direction the airplane is flying, especially during landing and

takeoff.

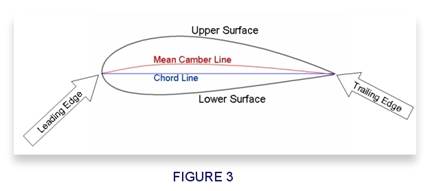

Figure 3 shows a typical airfoil geometry with the important components

labeled. The Upper

Surface is

the wing section skin on top, from the leading edge to the trailing edge.

The Lower

Surface is

the bottom wing section skin that goes from the leading edge to the trailing

edge. Mentioned already is the chord line, which is an imaginary straight line

between the leading edge and trailing edge; this is used for measuring/setting

Angles-Of-Attack (see Figure 2).

The chord line

should not be confused with the mean camber line, or meanline for short.

The mean camber line is an imaginary line that divides the airfoil into equal

(roughly) upper and lower halves. On a symmetrical airfoil, the mean camber

line is thesame as

the chord line. However, if you bow the airfoil upwards, you are adding

"camber" to the airfoil. A unique characteristic of airfoils with

camber is that they produce lift at zero degrees Angle-Of-Attack. The more

camber, the more lift. Of course, there is an associated cost of more drag and

more pitching moment (we'll get to that later) as well.

A perfect airfoil would

allow you to change the mean camber during flight; providing ample camber for

takeoff and landing, but very little during cruise. Fortunately, there is a

simple method for doing this without resorting to bending or flexing the

structure. Instead, we droop down the aft portion of the wing section using a

hinge. This device is called a flap and temporarily adds camber to the wing

section. Flaps allow our wing section to have lots of camber during takeoff and

very little camber during cruise. If the flaps also extend backwards while they

droop, then they also provide increased wing area, making for an amplified

lifting effect.

In Part 3 of

this primer series, we will discuss lift and drag calculations in more detail.

We will discuss their respective coefficients, which allow us

to compare the performance of different airfoils on a common scale.

HOW MUCH LIFT AND DRAG CAN A WING GENERATE?

Many

smart people asked this same question in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. They

wanted a simple formula to predict the forces ahead of time. The main

challenge to finding a simple formula was that the lift force was not just a

function of one

thing; it

was a function of many things.

Here's

a summary of information those early pioneers knew about:

- As

the density of air increases, the lift force also increases.

- As

the wing area increases (birds-eye view), the lift force also increases.

- When

airspeed is doubled, the lift force is quadrupled!

With

these trends in mind, those smart engineers and scientists stated that Lift was

proportional to the air density, proportional to the wing area, proportional to

the square of the velocity, and was somehow related to the wing cross-section

itself. But even after they figured all this out, there still wasn’t an exact formula.

For example, they couldn’t say that lift was exactly equal to the

product of speed, density, and wing area. The best they could do was say that lift was sort of equal to that product. Kindof equal.

But not exactly equal to a combination of all those things.

In

this situation, engineers often state a problem in outline form using a

proportionality symbol called tilda, or

"~". Here's a pseudo-equation for Lift:

LIFT ~ DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA

To

fix this lack of exactness, they did what any good engineers would do; they

used something called a proportionality constant, also sometimes called a coefficient. Generally,

these are special numbers used to make our answers agree with what we measure

in the real world; especially with natural phenomena where many of the lesser

influences are lumped into that single special coefficient. Non-engineers can

think of this as a fudge factor,

but it's a very well thought out fudge factor. You can represent this coefficient

with any letter of your choice; historically for Lift we've used the letter C

with a little "L" as a subscript: Cl

Let's

take another attempt at making a more exact Lift equation:

LIFT = Cl * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA

Stop

the presses! You may wonder where the one-half (0.5) came from. That's actually a

result of developing the formula using a more advanced method called dimensional analysis, but I won't dive

into that process right now.

Similar

to the Lift force equation, we can create formulas for the drag force and

pitching moment as well. The only real difference is that the pitching moment

includes the extra factor of chord-length at the end:

DRAG = Cd * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA

PITCHING MOMENT = Cm * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA *

CHORD

You

can probably see the problem already. The formulas are great and all, but we

still can't use them because we don't know the values of the coefficients (Cm and Cd). This is where

a wind tunnel really helps us. I'll cut to the chase: the coefficients are a

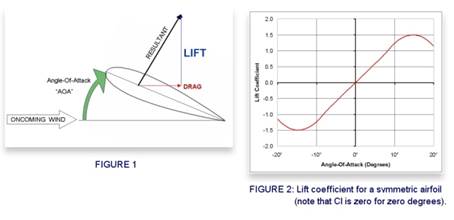

function of the Angle-Of-Attack of your airfoil section.

Fortunately,

our engineering ancestors tested thousands of airfoil sections in wind tunnels and they created

wonderfully useful charts showing how the coefficient values change as a

function of Angle-of-Attack, or AOA.

See Figure 1 below for an illustration of this parameter. When given a specific

AOA, we can look at a chart like Figure 2 below for our airfoil to quickly

discern what the coefficients should be.

Coefficients

are helpful for many reasons. First of all, with just a little bit of

performance data on our two-dimensional airfoil, we can extrapolate the

aerodynamic performance of a new and untested wing. Secondly, coefficients also

make it easy to make comparisons between two different airfoils. For example,

if our airplane wing needs a lift coefficient of 0.3 to stay aloft, we can

choose the airfoil that produces theleast amount of drag at that lift coefficient. And

coefficients are fairly robust. You can usually trust that a chart of

coefficients will remain unchanged. Except, of course, for

one small problem. To apply the proper coefficients, we must make sure

that the original data was captured at the same Reynolds Number. We’ll talk

about that soon, but let's elaborate on these coefficients.

ESTIMATING LIFT, DRAG, & PITCHING MOMENT

To

estimate any of these forces or pitching moments (torques), you need to have

real numbers for the coefficient. If we can measure the wing sections'

Angle-of-Attack (See Figure 1 above), then we can quickly look up the coefficients

from charts similar to those shown in Figure 2 above.

LIFT CALCULATION EXAMPLE

Recall

the formula for Lift:

LIFT = Cl * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA

Are

these terms confusing? Let me explain them.

As

we just discussed, the Cl term

is called the lift

coefficient.

It is a function of Angle-of-Attack and is generally a

straight line with a slope of

0.11 per degree (AOA). It varies from airfoil to airfoil, but it usually peaks

at an angle of about 15 degrees and starts to drop after that. That drop-off

phenomenon is called STALL.

The important thing to remember is that, unless you’re operating near the stall

region, every one-degree increase in angle-of-attack increases the lift

coefficient by about 0.11.

Of

special note, the 0.11-per-degree slope stays fairly constant until you include

3D effects (wingtips, etc...). We can add flaps, slats, and other doohicky’s to our infinitely-spanned wing section, but the

lift-per-degree slope doesn’t

change. Yes, those additional devices will move the line around the chart, but

they won’t change the slope.

Air density is

measured in something strange called slugs. That’s right; slugs. In the metric

system, mass is measured in Kilograms. In the English system (foot, inches,

pounds, etc…) we use slugs. On the surface of the

earth, one slug weighs about 32.2 pounds. Confusing stuff, right? Just know

that the density of air at sea level is roughly 0.002377

(double-oh-two-three-seven-seven) slugs per cubic foot.

SPEED is

the velocity of flight in feet per second. Not miles per hour.

AREA is

the area of the wing in square feet as seen from a birds-eye view above. We

call this type of area the planform area.

NOW BACK TO THE LIFT EXAMPLE...

Let’s

put an imaginary symmetric wing-section

model in the Ohio State University’s three foot by five foot wind tunnel. It

will span the entire width of the test section (wall to wall); that means the

span will be 3 feet. Our chord length is roughly 2 feet. That gives us a wing

area of about 6

square feet.

Ohio

State University is at an altitude of roughly 900 feet above sea level so the

density today is 0.002315 slugs per cubic foot (I got that from an internet

weather website). We turn on the wind tunnel fan and blow air over the model at

a speed of 100 feet per second. I forgot to tell you that we used the most

common airfoil ever produced: the NACA 0012 symmetrical airfoil section. We’ve

manually set the Angle-of-Attack to zero degrees as shown in Figure 3. With no

angle-of-attack, Figure 2 shows that our lift coefficient is roughly

zero.

After

plugging those values into the Lift Equation, it looks like this:

LIFT = Cl * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA

LIFT = 0.0* (0.5) * 0.002315* 100

* 100 * 6 = 0 pounds

We have no lift. This is expected for a symmetric airfoil at

zero degrees Angle-of-Attack. Your assistant increases the airspeed. Still no

lift, but your load cells have registered an increase in the drag force.

It

looks like we’re going to have to change something other than airspeed to generate

lift out of this wing-section. We can do that! Ask your assistant to turn the

knob that manually tilts the nose of the wing-section upward (i.e. increases

Angle-of-Attack). After some finagling of the equipment, we note that the

wing-section is now rotated upward at 5 degrees Angle-of-Attack similar to the

airfoil in Figure 1. According to the chart in Figure 2, such an

Angle-of-Attack will give us a lift coefficient equal to about 0.55. With that

information and our Lift equation, we can predict that our wing wection will produce a lifting force:

LIFT = Cl * (0.5) * DENSITY *

SPEED * SPEED * AREA

LIFT = 0.55* (0.5) * 0.002315* 100

* 100 * 6 = 38.2 pounds

With

the prediction in hand, we look at the Lift Force Meter on the wind tunnel and

we note a reading of about 38 pounds. Success! Using previously obtained

aerodynamic data, we were able to predict and reproduce the lift force

experienced by our wing-section model inside a wind tunnel.

DRAG CALCULATION EXAMPLE

Just

for fun, let’s continue increasing our Angle-of-Attack. The lift force will

continue to increase until we reach a special angle called the Stall Angle. Often,

this occurs when the Angle-of-Attack is near 15 degrees. At that point, the air

no longer flows smoothly over the wing. The lift force will decline after that,

but the drag force will skyrocket!

For

the previous example, we used a symmetric airfoil which will not produce lift

at zero degrees Angle-of-Attack. Had we used any other airfoil with camber, we would have

produced a lift force even at zero

degrees angle-of-attack. A symmetric airfoil was chosen for simplicity.

Let’s

reduce the Angle-of-Attack down to a modest 5 degrees where we know the lift

force is around 38 pounds. At this condition, how much drag force is being

generated?

For

drag, we use a similar formula where the Cl is replaced by Cd, the

so-called drag

coefficient. One

thing to note; we read the drag coefficient information from a different chart

called a Drag

Polar.

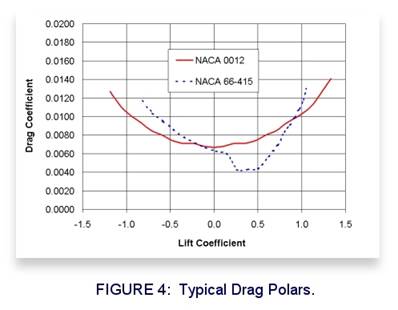

Shown in Figure

4,

the Drag Polar illustrates how the drag coefficient varies as a function of the

lift coefficient.

Here

is the equation for drag:

DRAG = Cd * (0.5) * DENSITY *

SPEED * SPEED * AREA

Recall

that the Angle-of-Attack is 5 degrees and the lift coefficient is 0.55. Since

we know the value of the lift coefficient, we can use the Drag Polar chart

shown in Figure 4 to look up the drag coefficient which has a value of roughly

0.0075. Drag coefficients are always shown with four decimal places. When we talk

about Drag Coefficients, we consider the ten-thousandths place to be a

single Drag Count. For example,

the NACA 0012 airfoil shown in Figure 4 has a drag coefficient of seventy-five Drag Counts at the

same time that the lift coefficient is 0.55.

Estimating

the drag force on our wall-to-wall wing-section model is fairly straight

forward. Here is the calculation:

DRAG = Cd * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA

DRAG = 0.0075 * (0.5) * 0.002315 * 100

* 100 * 6 = 0.5 pounds.

If

we have a real wing which is not infinitely long, we must modify the 2Ddrag coefficient with an

additional "3D" term, as shown here:

Cd_3D = Cd_2D + [ Cl * 0.5 / (Pi * e *

ASPECT_RATIO)

Cl is

the lift coefficient, Pi is 3.14, e is the Oswald Efficiency Factor (use 0.8)

and the ASPECT_RATIO is the wingspan divided by average chord length.

PITCHING MOMENT

What

about the pitching

moment coefficient?

The moment is often forgotten by many introductory texts even though it is very

important especially for trim drag. For those not familiar with the word

“moment”, that is the engineering term for the common word torque.

Remember: Moment is a fancy word for torque.

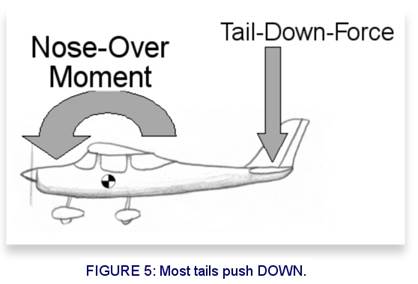

As

a wing flies through the air producing lift, it also has a tendency to create a

nose-over moment or torque. In other words, the airfoil wants to flip end over

end; often called nosing-over. This is not a desired effect. Some airfoils

produce a very strong negative (nose-down) moment and some do not. Most tails

push down to counteract the airplanes desire to flip nose over (See Figure 5

below).

History

has shown that the (pitching) moment coefficient stays relatively constant when

measured about the 25% wing chord position. Because of this, almost all data

about airfoil pitching moments are referenced to the 25% chord position.

Engineers call this the “Quarter Chord” location. The equation for moment is similar to

the lift and drag equations, but it has the actual chord length thrown into it:

PITCHING MOMENT = Cm * (0.5) * DENSITY * SPEED * SPEED * AREA *

CHORD

When

a pilot lowers his flaps, both the lift and pitching moment increase greatly;

the nose-over-tendency is often amplified.

“If

that’s true,” I’m often asked, “then why does the nose on my Cessna pitch

upward when I drop the flaps?”

This

strange effect is caused by two things that happen when we lower the flaps on a

high-wing Cessna. The nose-over pitching moment increases greatly, but the

flapped wing is also deflecting the trailing air at a much more downward angle.

The downward flow of air behind the wing is hitting the horizontal stabilizer

at a much steeper angle; an "artificial" angle of sorts. This results

in a strong downward lift coefficient on the tail, which essentially pushes the

horizontal stabilizer down harder than the wing wants to flip nose down. That’s

why the nose pitches up when we drop the flaps on some high wing

aircraft.

In

Part 4 of this primer series, we will discuss Reynolds Number and laminar flow

airfoils.

PART 4:

OZZY

REYNOLDS AND HIS NUMBER

You

wouldn't give an adult-sized dose of medicine to a baby because the volume is

not scaled correctly for their size. A similar thing happens with aerodynamic coefficients. Just because

you obtained the coefficients from a small model in a wind tunnel test does not

mean they automatically apply to a full-scale aircraft. To ensure that the data

obtained from a wind tunnel is applicable to a full-scale aircraft, all we need

to do is match Reynolds

Numbers.

To better explain this concept, let’s go to the aerodynamics laboratory.

We’re

now standing next to a wind tunnel. Inside, there's a quarter-scale model of an

airplane mounted on a force-measuring device. Let’s call this airplane the Wessna Worrier. The wind tunnel speedometer shows me that

the air inside the wind tunnel is traveling at almost 160 miles per hour. I’m

just a mediocre pilot, but even I know this airplane could never go that

fast. So I ask the operator about this speed discrepancy and he says, “Oh, we’re just trying to match the Reynolds Number to full scale.”

Huh?

The

world of engineering is filled with special numbers named after people long

gone whom you and I will never meet. One of these people was Osborne Reynolds, an Englishman

from the late 1800’s. Mr. Reynolds was obsessed with watching colored dye flow

through pipes. He was especially interested in how the dye would start out

flowing as a smooth streak (Laminar)

and invariably break down into eddy-filled craziness (Turbulent). The same phenomenon

can be seen with cigarette smoke rising from an ashtray. Reynolds didn’t know

it immediately, but he was really studying the concept of boundary layer growth; a subject that

is of paramount importance in aerodynamics. In the absence of boundary layer

phenomena, aerodynamics is downright simple. Unfortunately, major things like

top-speed and maximum lift are very dependent on boundary layers.

At

the beginning of the 20th century, a German researcher named Ludwig Prandtl formulated the equations needed to describe how

boundary layers grew. In short, they get thicker and messier as they progress

downstream. Prandtl used a subset of the previously

known Navier-Stokes equations for his methodology. Very

complicated stuff, but Prandtl was a very smart guy.

The

thing to know is that the Reynolds Number (Re) contains a summary of flow information. It conveys

nearly everything you need to know about a certain flow condition and it

doesn’t even have any units. No feet. No inches. No pounds.

Nothing. It is a product of the fluid density, fluid

velocity, important (characteristic) length, and the reciprocal of the fluids’

viscosity. Think of it as a meat grinder where you pour all the environmental

flow conditions in one end and the unitless Reynolds Number plops out

the other end.

In

essence, when you match the model Reynolds Number with the full-scale Reynolds Number, you are

effectively removing the scale effect.

THE SIZE OF YOUR REYNOLDS NUMBER

With

a little experience, you can get useful information about a fluid flow just

from knowing the magnitude of

the Reynolds Number. For example,

if you see wind tunnel data taken at Reynolds Numbers of 200,000 or less, it is

safe to assume that those airfoils were meant for either model airplanes or

high-altitude airplanes; both conditions lead to small Reynolds Numbers. If the

data was taken with Reynolds Numbers between about 500K and 6million, it

usually applies to general aviation; this is the regime where a lot of

historical and freely available wind tunnel data was taken. When the Reynolds

Number goes above about 9million, we’re usually talking about fighter jets or

passenger airliners. Of course, this is just a rule of thumb and subject to

debate.

HOW TO CALCULATE THE REYNOLDS NUMBER:

1. Find out what your velocity is in

feet per second. To do this, multiply MPH by 1.4667 or you can multiply KNOTS

by 1.689.

2. Find out what your air density is.

Remember that this changes with altitude and it must

be in slugs per cubic foot. You can use the WingCrafter

module in DesignFOIL to find the air density at

altitude. For simplicity, 0.002377 slugs per cubic foot is

used for a sea level density.

3. Find out the viscosity of air. Use

0.00000037373 (it’s a REALLY small number)

4. Decide what the important dimension

is. For wing-sections, that dimension is the chord length. For round objects

like spheres, the dimension is the diameter.

Using

the above information, use this equation:

REYNOLDS NUMBER = DENSITY * SPEED * DIMENSION / VISCOSITY

The

equation is very telling - the numerator (top portion) is made up of momentum

effects and the denominator (bottom portion) is made up of viscosity effects.

As a Reynolds Number grows larger, it implies that the momentum effects of the

fluid are becoming more important that the viscosity effects.

If

you’d rather avoid the above math, here’s a simplified formula for sea level Reynolds

Number using mph and feet:

REYNOLDS NUMBER = 9360 * SPEED(in mph)

* DIMENSION (in feet)

The

mention of Reynolds Number implies "the

appropriate use of a given set of wind tunnel data." It’s easy

to think that any coefficient data that you get from a wind tunnel applies to

the full-scale airplane at the same speed. As we've learned, though, the coefficient

data is only “good” for the Reynolds Number that it was taken at. So, to get

full-scale Reynolds Number data from a wind tunnel, you have to increase the

airspeed over the model in an effort to match what would be the Reynolds number

on a full scale model.

For

example, to obtain aerodynamic coefficient data ( Cl,

Cd, Cm ) from a half-scalemodel that is applicable to the full-scale aircraft,

we would have to double

the airspeedover the model in an effort to equate the

Reynolds Numbers. Or we could double our air density instead, but that is very

expensive and difficult to do. So in summary, if we cut the wing chord in half,

the Reynolds number also gets cut in half. To compensate, we’d have to double

the airspeed to keep the same Reynolds Number. It can be very confusing

sometimes.

Reynolds Number Anecdote (It's true!)

A

friend of mine once tested an Estes model rocket in a

slow wind tunnel. Because the actual rocket was so small and our wind tunnel so

slow, he instead built a giant "model" of the rocket that was ten times LARGER than the

real rocket. At that scale, he could slow the airspeed in the wind tunnel to

one-tenth the speed that the rocket really flies at; this method gave him identical Reynolds

Numbers. Therefore, he could apply the Cl and Cd values that he got from the

wind tunnel directly to his flight performance estimates, even though the model

size was very different.

A TECHNIQUE FOR REDUCING DRAG

Stories

come and go about the legendary airfoils on the WWII era P51 Mustang. It is often

said that the airplane’s high speed was a result of its so-called “laminar

flow” airfoils which you are about to learn about. While it is true that the

wing drag was probably less than contemporary aircraft of the time, the metal construction at the time

prevented those airfoils from reaching their full potential regarding drag

reduction. One of the larger contributors to the extreme speed was probably the

enormous power from the Merlin engine.

Methodically-developed

laminar flow airfoils have been around since even before WWII; they were the

brain child of Eastman

Jacobs,

an engineer at the NACA during the 1930’s. In the preceding 30 years, smart

people like Germany's Ludwig Prandtl learned that

drag could be reduced by controlling the shape and growth-rate of the layer of

thin fluid just above the wing surface. This region of fluid became known as theboundary layer because it

was the boundary between

the wing surface (airspeed = zero) and the outside freestream (airspeed = not

zero).

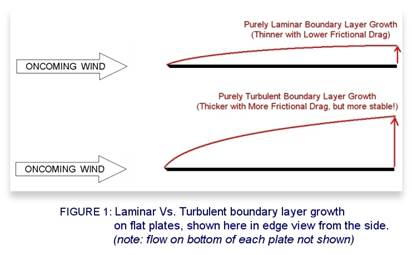

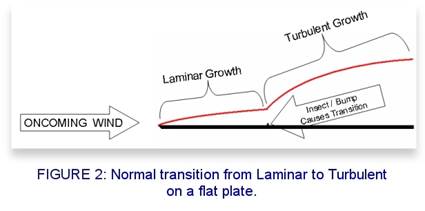

For

the following explanation, refer to Figure 1 which shows the two common types

of boundary layer growth on a flat plate.

The viscosity of air, or

its' "gooeyness", plays a very important role in the thin region of

air just above the surface of any moving object. On a microscopic level, even

the most polished surface still looks like a mountain range. Air molecules that

try to maneuver these peaks often get stuck and donate their momentum to the

mountains themselves (i.e. the wing) in the form of heat and friction. Just prior to

being halted by the surface of the wing, these molecules of air had been moving

at the speed of the aircraft. The speed changes from full aircraft speed to

zero over a tiny distance.

On

a larger scale this effect is felt as a friction force tugging on the wing

surface (i.e. drag). Again, the velocity of the air in direct contact with the

wing is zero. As we move away from the surface, the speed of the air

accelerates quickly to match that of the freestream flow. Because this extreme

acceleration takes place over a height of just a few millimeters, the viscosity

of air is very important.

A

good way to picture this is to envision traffic on a seven-lane freeway in Los

Angeles. The far-right lane is where cars are entering and leaving the traffic

flow. They are moving slowly and may even be stopped. As you change

lanes away from the slow lane, the traffic moves faster and faster until you

reach the fast lane where the car velocities are highest, hardly affected by

the slow lanes at all.

At

first, the velocity-change between the bottom and top of the boundary layer is

done smoothly and produces a small amount of friction drag on the airfoil. The

layers of air in the boundary layer flow smoothly over one another without any

swirling. This type of boundary layer is called Laminar and

produces very little friction. Think of it as a stack of highly polished playing cards being

dragged over carpet. The cards glide effortlessly over each other while the

bottom cards are left behind. The trade-off is that this low-friction laminar

boundary layer is not very stable and will switch to a draggier, yet more

stable, turbulent boundary layer at the slightest hint of a surface

imperfection which trips the

laminar flow. And in the real world, the boundary layer usually starts out

laminar and transitions

to turbulent as

shown in Figure 2 below.

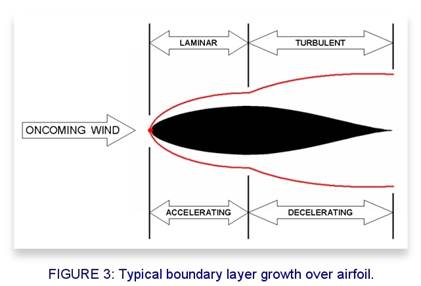

The

boundary layer growth on an airfoil is more complicated than a flat plate. The

difference, shown in Figure 3,

is in what causes transition to occur. Imperfections will still trip the

laminar boundary layer, but airfoils have the additional phenomenon of the pressure gradient. The pressure

gradient refers to how the pressure is changing as we march downstream from the

nose of the airfoil. If the pressure gradient is negative, we feel like we are

being swept along faster and faster (like a canoe being pulled toward a

waterfall). When the pressure gradient is positive, we feel higher and higher

pressure and a certain feeling of "pushback" from the air as we march

downstream (like that same canoe going from a high-speed river into a calm

lake).

On

the forward portion of an airfoil, the pressure gradient is negative and the

air is accelerating downstream; a perfect habitat for a laminar boundary layer. However, when the

air stops accelerating and begins decelerating, we get a positive pressure

gradient. That causes the laminar boundary layer to transition to a turbulent

boundary layer. The flow loses its smoothness and starts

filling with eddies, causing the outside air to start mixing with the

already formed boundary layer. This “turbulent” portion of the boundary layer is

thicker and produces relatively higher friction drag compared to the smooth

laminar portion of the boundary layer.

The

following list of steps outlines the general birth and death of a boundary

layer on an airfoil:

1. The oncoming air slams into the

leading edge and stops. This point (shown as a red dot in Figure 3)

is called the Stagnation Point. This location serves as a dividing

line. The air beneath goes below the airfoil. The air

above the Stagnation Point goes over the top of the airfoil.

2. As the airflow leaves the

Stagnation Point, it accelerates past both the upper and lower surfaces due to

the strong negative pressure gradient. This unique flow forms a laminar boundary

layer. It continues to grow in a laminar fashion until the minimum pressure

(max velocity) is reached. Unless previously tripped by a surface imperfection,

this is the likely transition point.

3. After transition, the boundary

layer becomes turbulent, eventually leaving the airfoil at the trailing edge.

There

are a few known variants to this script. If the flow condition is at a very low

Reynolds Number, the laminar boundary layer sometimes skips the

transition-to-turbulent phase and instead separates, never to be heard from

again! Sometimes it immediately reconnects forming a thicker turbulent boundary

layer than normal. The region between the laminar separation and the turbulent

re-connection looks like a bubble and is often called a Laminar Bubble. If the laminar

bubble fails to re-establish a viable turbulent boundary layer, the air just

leaves the airfoil at that point and the wing flies around in a semi-stalled

condition.

If

you've done any radio-controlled airplane

flying, you may have seen airplanes with zig-zag tape on the upper surface of

the wing. The purpose of such a boundary layer tripping device is to combat the

laminar bubble problem that occurs at model flight scales. Those pilots are

taking matters into their own hands and forcing that sensitive laminar boundary

layer flow to trip itself into a more stable turbulent boundary layer (to avoid

separation). After all, a draggy turbulent layer is better than separation and

stall.

Using

trip devices (trip strips, vortex generators, etc...) can force an otherwise

laminar bubble to stay attached to the wing long past it's

normal stall angle - turbulent boundary layers tend to be "stickier"

than laminar boundary layers. Some academic cargo-payload competitions can benefit

from this effect by flying at higher Angles-of-Attack, thus carrying more

weight than just a clean wing.

Keep

in mind that the boundary layer thicknesses depicted in Figure 3 are greatlyexaggerated. Here is what

you can expect in the real world: say you are flying along at 100knots at sea

level staring at the pretty sailboats. Your airplane's wing has a 5-foot

(152cm) chord. The airfoil design consistently produces laminar airflow over

the first 20% of the surface, with the rest being turbulent. The laminar

boundary layer thickness would be about 0.060" (1.5mm). The turbulent boundary layer thickness could grow

from 3/8" to 1/2" (9.5-13mm) at the trailing edge of the wing.

Over

the years, we have discovered that creating and maintaining laminar boundary

layers is much trickier in real life. Unlike the mirror finishes of wind tunnel models, real airplanes

are very dirty. Have you ever seen the leading edge of a wing from a full-scale

airplane? It is coated with insect guts - laminar flows don't like insect guts.

In

Part 5 of this primer series, we will discuss laminar flow airfoils in detail.

Chapter 5

LAMINAR FLOW, BY ACCIDENT

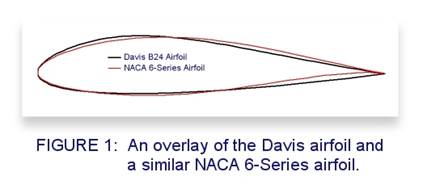

During

the 1930’s a self-taught aerodynamicist named David R. Davis went to the trouble

of patenting an airfoil design, which he called the “Fluid Foil” (US Patent

#1,942,688). He considered his design special because it exhibited lower drag

than most other common airfoils, but he wasn’t sure why. His timing was impeccable

because fortunately for Mr. Davis, the Consolidated Aircraft Company was

looking for a marketing trick to make their new aircraft stand out from the

competition; a unique low-drag wing was just the ticket. After verifying the

low-drag performance of the Fluid Foil in a wind tunnel, Consolidated licensed

the airfoil patent from Mr. Davis in 1937. The Fluid Foil eventually found its

way into the wing design of the B-24 Liberator bomber during WW2. (Ref: Vincenti, 1990)

Without

knowing it, Mr. Davis had inadvertently invented the first airfoil to achieve

low-drag through encouragement of a laminar boundary layer, the rarely seen smooth airflow

that briefly exists before the higher-drag, turbulent boundary layer takes

over. The concept of the laminar boundary layer was discussed in detail in Part

4 of this airfoil primer series.

Consolidated

Aircraft went on to build over 19,000 of the B-24 bombers, putting it ahead of

the venerable B-17 in production count. Although many people consider the P-51

Mustang to be the first aircraft to use laminar flow airfoils, the truth is

that the B-24 was the first, albeit accidental, aircraft to use laminar flow airfoils.

The true significance of the P-51 wing was that it was the first to intentionally use the

new scientifically developed NACA 6-series laminar flow airfoils.

As

interesting as these historic facts are, it’s even more amazing to learn that

neither of these airfoils actually produced much usable laminar flow when

finally integrated on real world aircraft. In fact, they were probably just as

turbulent as every other plain vanilla airfoil out there. We can forgive the

designers though - it's one thing to base all of their

data on finely polished wind tunnel models and it's another thing to build real

wings out of sheet metal, rivets, bucking bars, hammers... all with a war

raging against them. Add mosquito guts onto the leading edges and they had

little chance of establishing much of a laminar boundary layer at all.

I

don’t mean to downplay the development of laminar flow airfoils on metal

aircraft. Analytically, it was a significant leap for the early engineers to

"backward-solve" the formulas used for analyzing airfoils. Rather

than starting with known surface coordinates and calculating the resulting

pressure distribution, the NACA personnel figured out how to take the desired pressure distribution and back

out the required surface contours!

Due

to modern day construction methods, stiff composite materials, and improved

laminar flow airfoil designs, there is renewed interest in the use of laminar

flow airfoils in general aviation. Most modern racing aircraft (such as the decambered NASA NLF used on Nemesis NXT) use some type

of laminar flow airfoil; often modified for proprietary purposes.

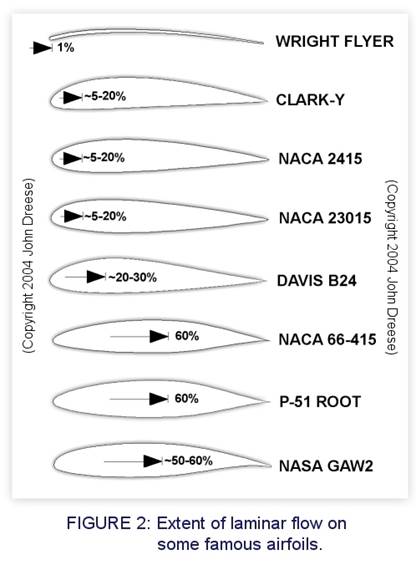

Laminar Or Not?

It

may surprise you to learn that all airfoils have some laminar

flow; even the airfoil used on the Wright Flyer. Granted, the laminar flow on the

Wright Brothers airplane only lasted a few percent of the chord length, but

there was some laminar flow. This brings up the question of how to classify

airfoils. Laminar or not laminar? As it turns out, the

answer is subjective.

Generally

speaking, for an airfoil to be considered a laminar flow airfoil, it must have

a favorable pressure gradient that extends past 30% of the chord length.

Laminar boundary layers are sensitive beasts and prefer to have the surface pressurecontinuously dropping as they

march downstream from the leading edge. When the surface pressure stops

dropping and begins to increase instead, the smooth laminar flow becomes

turbulent, fighting its way to the trailing edge. It’s easier to fall down a hill

than walk back up it again.

Figure

2 (below) shows a series of very common airfoils and how much of their chord

length will experience favorable pressure gradients (i.e. laminar boundary

layers) under ideal conditions. It is important to understand that extensive

laminar flow is usually only experienced over a very small range of angles-of-attack,

on the order of 4 to 6 degrees. Once you break out of that optimal angle range,

the drag can increase by as much as 40% depending on the airfoil.

Look

closely at the airfoils in Figure 2. The laminar designs in the lower half

exhibit extensive laminar flow (past 50%). They generally have sharper noses

which can result in a more unpredictable and sharp stall. However, the most

obvious trait is therearward placement of the maximum

thickness.

If you look at a wing edge-on and notice that the maximum thickness is far

back, you can bet that the airfoil is a laminar flow airfoil. I recommend that

you look at a Piper

Tomahawk wing

edge-on; you’ll discover right away that it uses a GAW airfoil.

The Quest for Low Drag

To

understand the great advantages of laminar flow airfoils, we need an

experiment. Imagine that we point a sheet of plywood into a 70 mph air stream

with no angle between the chord length and the relative wind (zero degrees angle of attack). If we could

magically force the boundary layer to stay 100 percent laminar from leading

edge to trailing edge, the frictional drag force would be roughly 0.6 pounds

(0.3 Kg). Now, if we flipped a switch to make the boundary layer completely

turbulent, the frictional drag force would jump to almost 3 pounds (1.4 Kg), a

net rise in drag of nearly 500 percent!

As

we can see from our simple plywood airfoil example, laminar boundary layers

result in much less wing surface friction compared to a turbulent boundary

layer. Remember that real world wings have a mixture of laminar and turbulent

boundary layers so the actual gains are on the order of 40 to 50 percent. The

ultimate goal of a laminar flow airfoil is one where we try to maximize the

laminar boundary layer while minimizing the turbulent boundary layer without

making the whole thing too overly sensitive to surface finish.

Consider

the builder’s ability to control the wing contour during construction and

flight. The surfaces of metal airplanes tend to “oilcan” during flight and this

can change the contour enough to trip the laminar boundary layer.

When

using composites, it’s important to keep close tolerances on the airfoil

contour. Contour control of a surface isn’t just a step-height allowance; it

depends on the chord length that it occurs over. Aluminum?

That's a tough challenge.

Speaking

of surface finish, I’ve heard stories of sailplane flyers actually scuffing the

gloss off their wings in a chord-wise direction from leading edge to trailing

edge with 600-grit sandpaper. If roughing up a surface reduces drag, that

typically means that the boundary layer was blowing off prematurely or had

laminar bubble issues; roughing up the surface helps both of those

situations (in some ways, it is similar to why dimples reduce drag on a golf

ball). Those problems are usually only experienced at very low Reynolds Numbers

(small chord wings flying at either slow speeds or high altitudes).

Anecdotal

stories of Indy race car guys rubbing baby powder on their cars to make it more

“slippery” have been circulating in the pits for years. The baby powder may

have felt smoother to their fingertips, but not to the air molecules!

Traditionally, a very smooth, clean, and highly polished surface will always

result in lower drag numbers. Wax it, don’t powder it!

Designing the Perfect Airfoil

You

may be thinking the same thing that NACA engineer Eastman Jacobs thought

back in the 1930’s. Why not design airfoils that only produce laminar boundary layers? That way,

you could have ultra low wing drag. Let’s take a look

at the numbers.

We

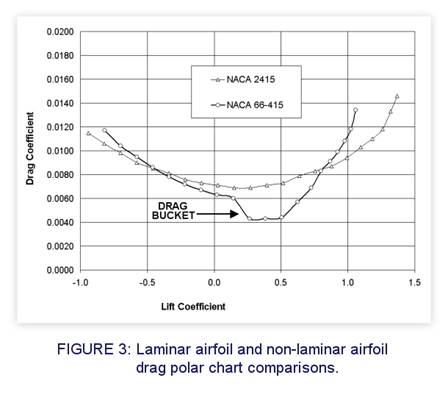

can quantify the reduction in drag due to laminar boundary layer development.

Figure 3 shows the reason why engineers have chased after laminar flow airfoils

for so long. This graph compares the drag polars of two

airfoils. One is for a typical airfoil (NACA 2415) and the other is for a

laminar flow airfoil (66-415). For the latter airfoil, we see that the drag

coefficient drops noticeably between a lift coefficient

of roughly 0.25 and 0.5. Your goal, as a designer, is to make sure that your

desired cruise lift coefficient falls somewhere in that drag bucket. (See arrow

in Figure 3)

Let’s

briefly recall what a boundary layer is from Part #4 of the Airfoil Primer

series. Even the smoothest surface looks like a mountain range when

viewed on a microscopic scale. As air flows past, hugging these surfaces, some

of the molecules get stuck and donate their energy to the microscopic mountains

themselves. These molecules of air that were originally moving with the speed

of the oncoming air flow are halted and brought to zero velocity right at the

surface! In engineering, this is called the “no-slip” condition. On a larger scale this

effect is felt as a friction force tugging at the wing surface.

We

can break it down even further. When the boundary layer begins forming at the

leading edge, it is flowing smoothly with each microscopic layer of air flowing

easily over the next like a deck of waxed playing cards sliding over one

another. This portion of the boundary layer produces very little drag force,

but unfortunately it only lasts until the air racing back along the airfoil

begins to slow down. With non-laminar airfoils, this typically happens within

five to twenty percent of the chord length. At that point, the laminar boundary

layer will begin mixing with outside air and become filled with small eddies.

These so-called turbulent boundary layers can be surprisingly stable, but the

trade-off is they produce higher drag than the laminar boundary layers

do.

Bubble Trouble

Prior

to now, you’ve learned that all laminar boundary layers grow up to become

turbulent boundary layers. When operating at very low Reynolds Numbers (less

than 100,000 for example), this transition to turbulent sometimes does not

occur. The boundary laminar boundary layer encounters the increasing pressure

and occasionally explodes away from the surface, never to be heard from again.

Sometimes it immediately reconnects forming a much thicker turbulent boundary

layer than normal. The region between the laminar separation and the turbulent

re-connection points looks like a bubble and is often called a Laminar Bubble. If the laminar

bubble fails to stay connected, the boundary layer leaves the airfoil at that

point and the wing flies around in a semi-stalled condition. This is very bad.

There have been a few rare cases where airfoils utilizing extreme laminar flow

have been so sensitive that even raindropscaused the boundary

layer to become unstable and blow off the surface, causing a stall.

You

may have seen radio controlled airplanes with zigzag tape on the

upper surface of the wing to combat these low Reynolds Number problems. Those

pilots are taking matters into their own hands and forcing that sensitive

laminar flow to trip itself into a turbulent boundary layer before separating.

After all, a guaranteed turbulent boundary layer is better than a chance of

separation and stall. Some folks have used this trick to get their

radio-controlled airplanes to carry more weight than normal during

cargo-carrying contests (hint, hint).

Luckily,

this tendency to go from laminar directly to separated

occurs less often as the Reynolds number is increased.

Key points to remember about boundary layer development:

1. Laminar boundary layers prefer air

that is accelerating (lowering pressure), but will convert to turbulent the

instant the air begins to slow down. Laminar means LOWER DRAG.

2. Turbulent boundary layers will

form from a laminar boundary layer once the air begins slowing down. Turbulent

means HIGHER DRAG, but not terrible drag. In the case of a golf ball, the

turbulent boundary layer actually reduces drag!

3. At very low Reynolds Numbers, you

may experience the draggy effect of laminar bubbles.

The Final Laminar (Plot) Twist

In

yet another twist regarding laminar flow airfoils on metal aircraft, they

turned out to be excellent performers for high-speed aircraft. High-speed, as in jet-aircraft. And it had nothing to do

with laminar boundary layers; rather it was a function of moving the minimum

pressure location significantly behind the leading edge. This resulted in an

increased critical

Mach number,

which allowed jet-fighters to go a little bit faster by minimizing supersonic

drag over the wings (even a subsonic airplane can experience pockets of

supersonic airflow on top of the wing due to local accelerations).

You

probably don’t have a jet engine though. So how can you make good use of

laminar flow airfoils? First of all, if you’re building a sheet metal wing and

won’t be flying past Mach 0.6 (about 450 mph), then don’t bother with extreme

laminar flow airfoils. Conventional NACA airfoils will work just fine for your

purposes. Van’s

Aircraft has

used the NACA 5-digit series very effectively on their RV models.

However,

if you are building a stiff composite wing, you may want to use a NACA 6-series

or one of the more modern NASA natural laminar flow airfoils. Just be sure to

keep those leading edges clean.

The

next time you visit Oshkosh, Sun-N-Fun, or the Reno Air Races, look at the

wings edge-on and try to guess if they are using a laminar flow airfoil. Ask

the pilot about it; they will appreciate that you noticed.

Congratulations

You've

reached the end of the five-part Airfoil Primer series. Let me know if these

have helped you.

Recommended References:

1. Theory Of

Wing Sections: Including a summary of airfoil data, Abbott and von Doenhoff, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60586-8.

2. The Illustrated Guide To Aerodynamics, Hubert “Skip” Smith, 1985, Tab Books, ISBN

0-8306-2390-6

3. Airfoil Selection, Barnaby Wainfan, self-published and available from EAA.

4. Basic Wing & Airfoil Theory,

Alan Pope, 1951, McGraw-Hill Book Company (does not have ISBN number).

5. History of Aerodynamics, John D.

Anderson Jr., 1998, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66955-3

6. What Engineers Know and How They

Know It, Walter Vincenti, 1990, Johns Hopkins

University Press, ISBN 0-8018-4588-2

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John

Dreese is the creator of the DesignFOIL airfoil

creation and analysis software package, available at:

If

you have any comments or questions, please feel free to email John at:

DesignFOIL@gmail.com

Twitter:

http://www.twitter.com/JJDreese/